It’s the evening of Mama’s 84th birthday, and although the entire family is present for the celebration, I’m sitting alone with her by the fireplace, listening intently as she slides easily into reminiscing about her parents. This doesn't happen often.

As a child, proximity to her maternal energy flooded me with anxiety, worries and panic that offered no logical source. She often, or always, thought ahead to every possible disastrous turn of events, cautioning and warning me until I experienced the lived trauma of catastrophes that could, might, but never did, happen. Until much later in my life, it never dawned on me to ask why she was so afraid. As it turns out, fear isn’t exactly the right word for the energy I sensed emitting from Mama; hyper-vigilance is more accurate.

We talk as she celebrates with birthday cake and diet coke, even though for the most part, soda of any kind is usually forbidden now. Sodium and congestive heart disease don’t mix. But tonight, she’s celebrating, and her eyes sparkle like a girl while as she chooses her words.

“I wish you could have known my mother, honey.” She’s clearing the cake off her tongue, and licking her lips.

“You know, my mom was only 15 when she fell in love with Daddy Red.” Counter-intuitively, she leans forward, reaching her mouth toward the fork, instead of the other way around.

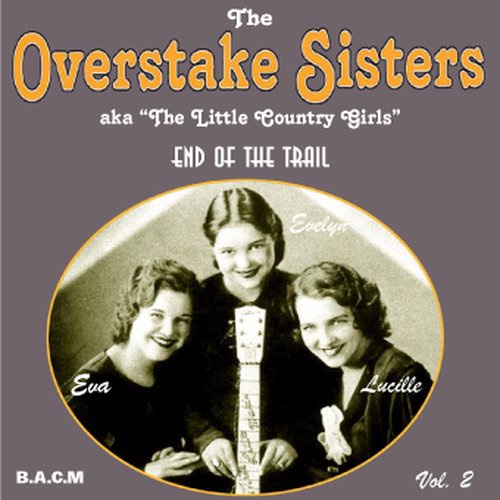

Switching topics, she throws in, “Mama Eva loved singing with her sisters. They had fans, and a manager… they told her Eva Overstake was too much of a mouthful, so her stage name was “Judy Martin.” A pause. “The sisters sounded so good together.”

I smile and nod quietly; I don’t want to interrupt her. Woefully content to leave my mother’s presence and wisdom behind in my early “adulthood,” for years, I barely asked her for anything I no longer believed she could give me. I stopped really seeing or hearing her for decades, and missed out on volumes of her stories. I don’t remember wondering what I might have given her. Grieving the loss of all of those stories, my eyes are open now, and I want to make up for lost time; with so little left, all I want is to lay my head on her lap, and drink her in.

Her words are paced a bit more slowly as she breathes her memories in…and out. I know she is editing for me, protecting me along with her parent’s secrets. She never dropped her guard.

“It wasn’t really so strange to marry so young then, even to a man 8 years older, but it would be frowned on now, I guess.” It would. Meeting a girl at 15, marrying at 16, and having children right away…I know it happened, but it’s shocking. Upsetting.

Randomly, she reminds me that she always thought she’d die the same year as her mother. I remember thinking when I heard this as a young girl that maybe I would die at 33, too. If that’s how it works.

Suddenly, she smiles brightly, youthfully, “I can’t believe I’m 84! I never thought I’d make it that long.” This is a victory to this woman who lives her days now bathed in gratitude and joyfulness.

Continuing the age-of-death summary, she adds, “Daddy Red was 58 when he died,” and I remember hearing about the funeral. I was 10 when my mother flew with Daddy and her sisters to Nashville to lay him to rest.

“Daddy Red” is the name his grandchildren called the enigmatic Clyde “Red” Foley who hosted and performed classic honky-tonk and heart-wrenching southern gospel music on the Ozark Jubilee stage in Springfield, Missouri. Later, he would become a fixture at The Grand Ole Opry. Red, an emotively astute, musical storyteller, often brought tears to the eyes of his fans. I hardly knew him at all, but I have come to understand through the family stories that at home, his temperament oscillated between warm and delightful to explosive.

My mother’s attention has waned for a few seconds, and I can tell that the next part is a bit of an emotional sinkhole.

“Mama Eva gradually stopped trying to sing professionally… we all sang together, sometimes. Off and on.” She pauses, and I sense an immeasurable loss for my maternal grandmother… as well as a wound through which my mother has incurred a kind of psychic, ancestral pain. This wound would eventually become more personal for her, the feeling of being the barely-there wife of her own movie star heart-throb. She made it definitively clear later in life that she wouldn’t trade being Debby Boone’s mother, Pat Boone’s wife, and Daddy Red’s daughter for anything. She radiated pride when she spoke of her part in their lives and successes.

“I was told more than once I could’ve had a career singing with my sisters, too,” she says. “People loved when we sang with Daddy Red.” My mother straightens the quilt on her lap, flattening and stretching until all of the untidy wrinkles and impediments disappear. She craves order.

She doesn’t tell me how much or how often her father drank, or about those nights there were incidents, some violent. I hear of these after Mama’s gone, a byproduct of the family telephone game.

Shifting her tone, she smiles, slightly. “I can’t remember if I told you this… Mama Eva was the first woman in Nashville to ever receive open-heart surgery in 1951.” She conveys this with an air of pride. It isn’t the first time I’m hearing about this significant historical event. She’s told me a few times, also writing it in tidy, cursive strokes on the backside of photographs, many times over the years, and I can tell it’s important to her.

“She was in so much pain,” she says, drifting away for a moment. She stares out into the room for maybe ten long seconds before stopping to take a drink of water. “She died soon after the surgery in November that year.” She swallows another drink of water. Her medication dries her mouth out to the extent that she can’t speak without hydrating every few minutes.

A deep breath, another sip, and she adds, “Before she died, she told me to take care of Jenny and Julie.” The comment drops with a thud; the sheer weight of it knocks the wind out of me. My warm and lovely aunts. Mama had just turned 17 when she lost her mother, and the weight of responsibility woven into that request is incomprehensible. We hear my sisters laughing from the living room, and my mother pats me on the leg. “You girls,” which is what she still calls her 60-something daughters, “I hope you’ll look after each other when I’m gone.” I nod again, an implied promise.

My mother never let go…of her sisters, of her daughters, of the loved ones for whom she felt responsible. I received this same messenger DNA as if through a transfusion, the feeling I would need look after everyone I love, or they’d never survive. A cup of kindness with a chaser of disparagement. My beautiful children are now compassionate, educated adults, no credit to me. They just are.

Mama once explained to me, carefully and intimately, that the things that were important to her as a mother came as a direct result of the losses she encountered as a young girl. She longed for her daughters to enjoy the security and stability that eluded the Foley girls: she wanted us to live in the same house and neighborhood throughout our childhoods, to be able to live down the street from our childhood friends without being uprooted and moved, and she wanted us to have a mother who was present for all of it. She gave it all she had, and she did better than I did.

And now I'm wondering, do we all see the needs of our children through the lens of the un-met longings of our childhood?

Do our loss-colored glasses distort our vision, our hearing, so that when our children are stating, clearly and urgently what they need, we can’t hear them?

Looking behind us, without reconciling our own losses or meeting those needs later in life, we render ourselves impotent, incapable of being present with our children in real time. We see them with our own ancient wishes superimposed over their sweet, vulnerable faces.

And what are the losses from childhood we keep buried under our skin?

This is the work, and if we can’t do it before we become parents, we may bequeath our dysfunction and heartache to our children, forever compelling them to adjust to our perennial longings…to meet our needs and silence their own. Until they can uncover these secrets for themselves, and plant the seeds of their own redemption.

My mother had a deep longing for connection with her God. We share that longing along with the massive reservoir of lasting love that continues to fill up the space between us. Still, I wish I had asked her to tell me more of her stories.

Gorgeous remembrance, Laury. So raw with longing and abiding love.

A powerful story, thank you! I found important answers here too, those ancestral needs I still carry.