I’m convinced my loose, ill-fitted leggings expose me as a yoga-neophyte. Did that sleek, perfectly-clad, model type behind me give me the once over? Even though she smiles warmly, I’m paranoid. My miss-matched cotton stretchy-pants and tank top give me away. As if my yoga skills won’t. I'm surprised (and relieved) to be given a free, first time pass to this high-end hot yoga class, but I don't want to be here.

It's 2018 in Irvine, California. The stringent desert heat is surprisingly intense considering it's only the very beginning of June. Atypically, my sisters and I have decided to go to a yoga class together. It's not atypical for them, just me. After taking extra time in the ladies room to pull my long hair into a tragically thinning braid, I tie a cotton, paisley-white bandanna around my forehead. I've purposely delayed entry to the broiler-room, so I can sneak in as the lights dim, positioning myself in the corner of the last row. From behind their tan-and-toned bodies in flexible down-dogs, I have a clear shot through the center of my sisters' thighs, stretching and pumping their legs rhythmically, all of them close to the front of the class.

It's 1000-something degrees inside the studio, and while I take classes on occasion at my gym, I'm a casual practitioner. I've taken three hot yoga classes in my lifetime. My sisters are regulars, and they're at ease laying out their mats, considering how much space they need, and placing their ample water bottles nearby. And towels, of course, for sweat. So much sweat. I can smell the heat.

As the instructor calls out transitions from one exasperating, extended pose to the next, I willingly-but-self-consciously do my best, choosing at times to sit still on my knees, to catch my breath, or to metaphorically hold up a white flag. I wobble out an hour later like I just toured the Grand Canyon on a mule, hoping the girls had missed the majority of my more awkward moves.

This is a familiar feeling for me, this sense that even though I consider myself to be somewhat fit and capable of agile movement, when I participate with my sisters in biking, hiking or exercise classes, I am usually catching up. Like yoga from the rear.

I have three sisters. We're close in age, with three and a half years between all four of us. We, (Laura/ me, Deborah, Linda and Cheryl) had our branding permanently mutated when my mother slapped the letter Y on the end of all of our names. I tried to change that a long time ago, leaning toward the more lyrical Laura, and away from the confusing spelling I still struggle to explain today. It didn't work; nobody wanted to participate in my name-change experiment except for one dear friend who empathized with my goal; after no one else followed suit, I told her to forget about it, and gave it up. Stuck with Laury.

As adults, my sisters and I have enjoyed and supported each other, remaining connected through a group text thread and weekly zoom meetups. We make each other laugh. My mother is doing a happy dance in heaven to hear this.

I'm the youngest of four, with all of the ramifications attached to that placement. They say the eldest child is likely to be perfectionistic, and the in-the-middle child (or children) may experience early self-esteem issues, resolving later in life as they become independent and stable. The youngest? It's not necessarily the picture one would want to paint of themselves. Extroverted, rebellious, often attempting to do bigger things than their siblings. Attention seeking.

Whatever.

For the most part, when I was small, I felt a bit like the odd man out, which eventually forced me to lead with my preferred self-perception as an outside adventurer and aspiring spiritual mystic. Basically, I just did what alone people do. I found games to focus on, and roles to play by myself. I was the brave fire starter, athletically skilled tree climber, the colored-pencil storyteller, and midnight escape artist, wandering the neighborhood under the light of the moon. Literally. Alone. I shudder to think about it now.

But this sounds more wild than it was; we lived on the corner of Beverly Drive and Sunset Boulevard. It was pretty quiet and mostly, there were old people in those houses. And celebrities. I sold school fundraiser candy bars door to door.

My sister Cherry, the eldest, must have experienced the full weight of the expectations of our first-time parents. Mewed for many years to the whipping-post of a punishing eating disorder, my big sister leaned painfully in the direction of the prophesied perfectionism. She wrote a book about it, Starving for Attention. And there was a follow-up book, a compilation of the letters she received from grateful readers that included her gentle and encouraging responses to every letter. Most recently, she studied to become a life coach, taught herself to play drums and joined a band in her neighborhood, and she lobbies in her Washington state district in the role of mental health advocacy. She loves people. Cherry is kind and strong, and at 70, she continues to reinvent herself.

My sisters are devoted to fitness, partly because it keeps them healthy and trim, and partly because it provides endorphins. It perpetuates feelings of well-being. I've given that a go a few times in my life, usually related to the idea that I needed to burn off calories.

A couple of times, visiting my sister Lindy in Orange County, we all dipped a little bit into biking, sometimes along a beach path together, other times in the gated community where she lived at the time. Lots of hills. I felt like my heart was going to beat out of my chest although to them, we were riding at a breezy pace; sometimes, I would have to slow down, or stop to catch my breath. I have an embarrassing memory… an image of me steaming with resentment when once, Lindy glanced at me from on top of a hill, and kept going. Couldn't she see I was struggling? To be fair, she's taught a variety of exercise classes, including spinning. She's used to leading, and pushing people to dig deeper. My daughter visited one of her classes a couple of years ago, my extremely fit, workout conscious daughter, and I remember her describing Lindy as "a beast." It's true, in more ways than one.

In the summer of 2001, Lindy's 24 year old son, Ryan, fell through a skylight, head first, down three stories of a stairwell. Devastation. His body was broken, and his tender creative mind suffered a traumatic brain injury that would alter the course of his life. After months with her son in an induced coma, and with their family, specialists and caregivers working together, Lindy had deepened her resilience again and again. Ultimately, with her husband Mike, she created a non-profit organization, Ryan’s Reach, and two respite homes that offer support for families that have been through traumatic brain injury crises of their own.

What else can I say about Lindy? She’s a tender badass who grew a powerful reservoir of compassion for others in the aftermath of tragedy.

In the early years, Debby and Lindy shared a room (along with their middle-child-status), knitting them together while simultaneously forming a bit of a moat around Cherry's island, and accentuating my (perceived) exile. Basically, we grew in different directions with different friend groups, as sisters do. The two eldest married a few months apart, around the time that Debby became famous. And not for nothing, her song, “You Light Up My Life,” held the number one spot on the Billboard Top 100 for 10 weeks, a record that wasn't surpassed for 15 years. At 21 years old, she performed the (winning) movie theme song at the Grammy's, the Golden Globes, and even the Academy Awards, with a song that became a wedding anthem at least a decade.

I followed her around like a puppy dog. Even then, she exuded so much grace and courage, standing on stages that dwarfed almost all of the others in the music industry. I could never imagine being that exposed. She never backed down, using each opportunity to learn, to grow as an artist. And as a human being. We (those who really know her) lean into her depth, and wisdom.

20 years ago, with those threatening divorce papers laying on my bed, I had spent the day doubled over in grief. My marriage can’t end. Not abruptly, not like this. I called Debby, and she listened to my story, and cried with me.

I asked, “What does love do now?"

Her answer...

"Oh, Laury… I think it lets go."

I really don’t believe she meant the marriage; maybe, just my fears about losing something that defined me. It took me years to love myself and my family enough to let go, but the words remain in my heart. Shit, maybe that should end up on my tombstone.

Or, maybe bigger lessons are on the way.

There's no shame in learning from those who can see further than we do, especially when they've paid the price to excel or survive, gathering tools along the way that are teachable and serviceable. I never learned how to do things the way the girls do them, know matter how in awe of them I am. That is, I haven't learned to duplicate them: their pace, their gifts, their athletic skills.

But I've learned resilience from them.

You can't miss Cherry's infinite compassion and optimism, in spite of her journey through (and beyond) shame and perfectionism. She’s joyful and endlessly evolving.

And I've studied Debby's humility and wisdom, in spite of having the rare distinction of being number one at the honest-to-god top of the world, as she’s continued to be a working singer/writer/entertainer who does her job with discipline and collaboration. She’s funny, generous and gritty.

And Lindy. She continues to care for her handsome, delightfully witty son - TBI didn’t steal his sense of humor. She wakes up every morning offering her services to the god that continues to sustain her, saying “God, I’m available.”

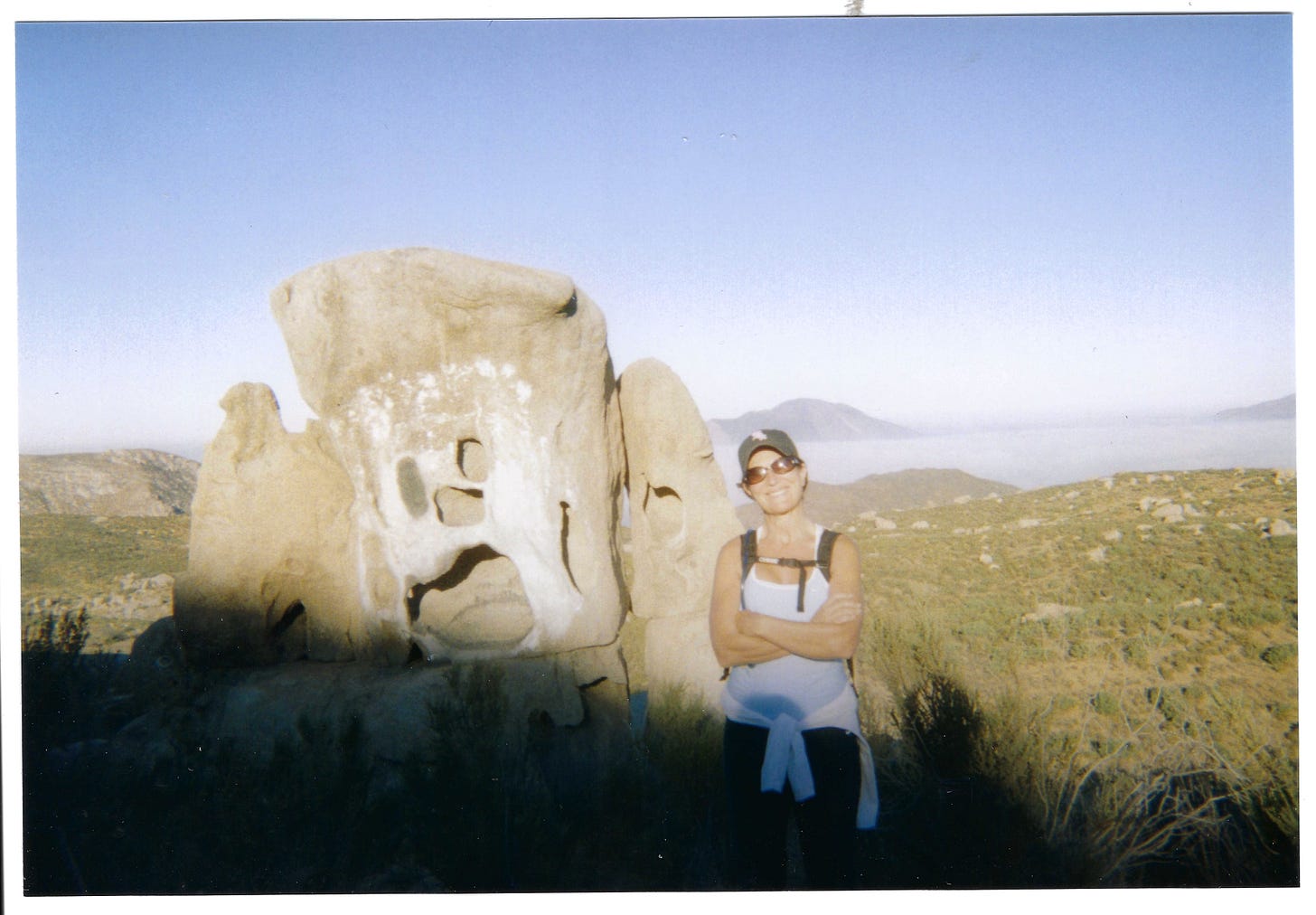

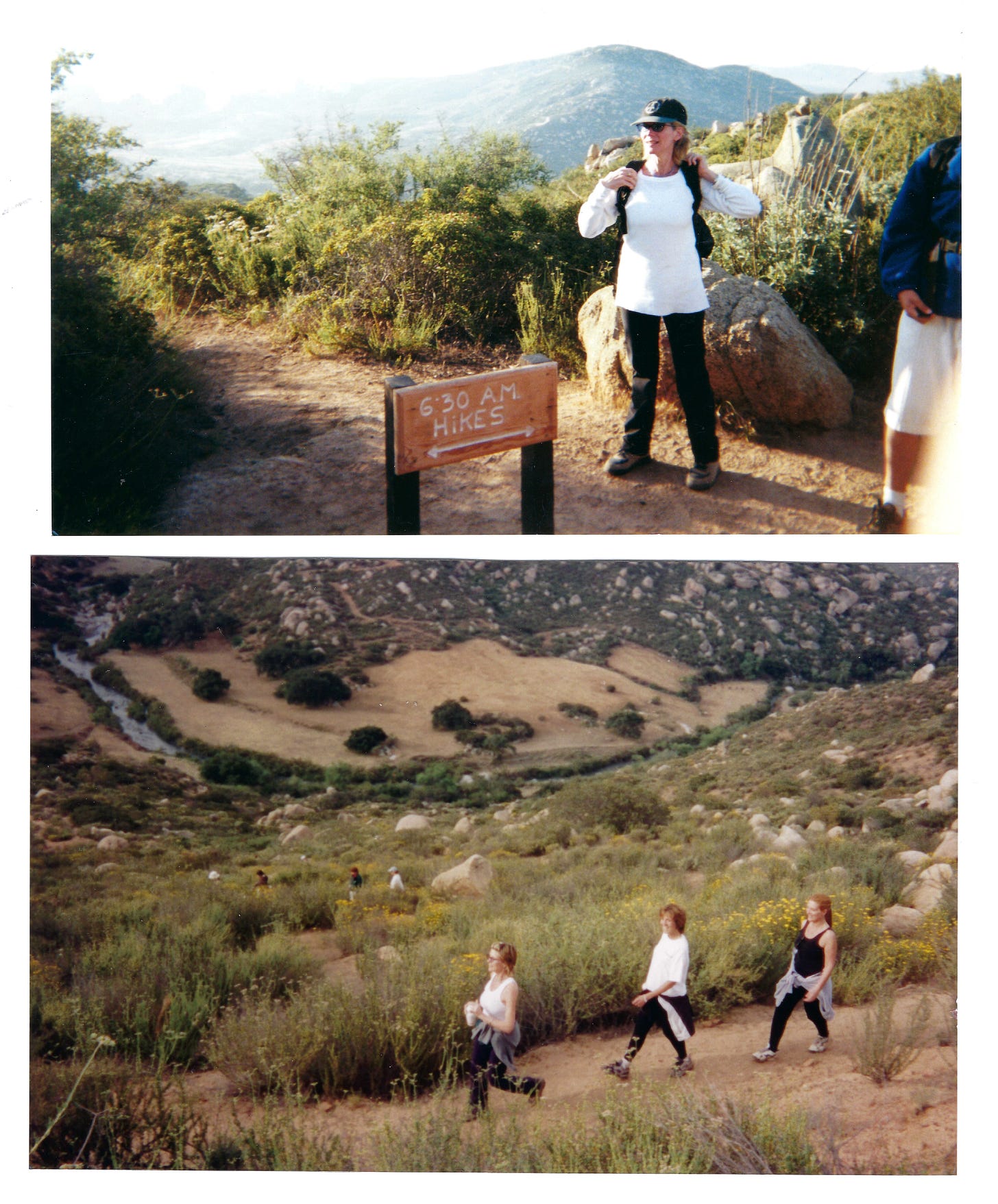

It's 1994, and I've trained for this. Mount Kuuchuma stands in front of us at our favorite retreat getaway, and this hike is a morning routine, starting at 6:30, early AF.

I can see Cherry, Lindy, and Debby up ahead, covered in hats and sunscreen, and they’re chatting, laughing, and telling stories. Talking about home life and movies, and it doesn't take long for me to be out of range to hear what they're talking about right now. I'm not talking anyway; I'm taking slow deep breaths before the real incline hits my lungs.

“You've been hiking inclines at home, Laury. You've got this.” I think the words out loud while everything in me wants to give up. It's not the work of the hike; it's the feeling, that feeling. Again. The girls, they’re stronger… they’re athletes. Whether I train or not, I still fall behind.

Just then, I look up, and yards ahead of me, every one of my sisters have stopped where they are, and their faces are looking back at me, smiling. I know, they probably want to push themselves, sweat a little more, and amp up their heart rates, but they pause. Debby calls down, "We just need to take a break." I know they don't need to rest, they just want us to arrive at the top together.

I pause, sip some water and drink in a gallon of air, wiping salty wetness from the sides of my eyes and temples. Looking up, I'm embarrassed, but grateful. Last, but not lost, and relieved to share blood with them.

How lucky am I to be reaching higher, further... forever catching up to these warrior women?